Whittier, California

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2008) |

Whittier, California | |

|---|---|

Greenleaf Street Whittier Village Cinemas Skyline of Whittier, California | |

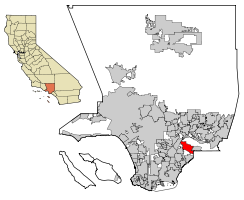

Location of Whittier in Los Angeles County, California | |

| Coordinates: 33°57′56″N 118°1′28″W / 33.96556°N 118.02444°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Los Angeles |

| Incorporated | February 25, 1898[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Joe Vinatieri |

| • Mayor Pro Tem | Jessica Martinez |

| • City Council | Fernando Dutra Cathy Warner Octavio Cesar Martinez |

| • City Manager | Brian Saeki |

| • Assistant City Manager | Shannon DeLong |

| Area | |

• Total | 14.66 sq mi (37.98 km2) |

| • Land | 14.65 sq mi (37.94 km2) |

| • Water | 0.02 sq mi (0.04 km2) 0.11% |

| Elevation | 367 ft (112 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 87,306 |

| • Rank | 98th in California |

| • Density | 5,824.9/sq mi (2,249.0/km2) |

| Demonym | Whittierite |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes[5] | 90601–90610 |

| Area code | 562 |

| FIPS code | 06-85292 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1652813, 2412260 |

| Website | www |

Whittier (/ˈhwɪtiər/) is a city in Southern California in Los Angeles County, part of the Gateway Cities. The 14.7-square-mile (38.0 km2) city had 87,306 residents as of the 2020 United States census, an increase of 1,975 from the 2010 census figure. Whittier was incorporated in February 1898 and became a charter city in 1955.[6] The city is named for the Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier and is home to Whittier College. The city is surrounded by three unincorporated areas sharing the Whittier name, West Whittier-Los Nietos, South Whittier, and East Whittier, which combined are home to a larger population than Whittier proper.

Etymology

[edit]In the founding days of Whittier, when it was a small, isolated town, Jonathan Bailey and his wife, Rebecca, were among the first residents. They followed the Quaker religious faith and practice and held religious meetings on their porch. Other early settlers, such as Aquila Pickering, also espoused the Quaker faith. As the city grew, the citizens named it after John Greenleaf Whittier, a respected Quaker poet, and deeded a lot to him. Whittier wrote a dedication poem and is honored today with statues and a small exhibit at the Whittier Museum; a statue of him sits in Whittier's Central Park, and another representing his poem "The Barefoot Boy"[7] used to reside by the City Hall and is now in front of the main library. Whittier never set foot there, but the city still bears his name and is rooted in the Quaker tradition.[6]

History

[edit]

The Gabrielino first inhabited the area.[8]

Whittier's roots can be traced to Spanish soldier Manuel Nieto.[9] In 1784, Nieto received a Spanish land grant of 300,000 acres (1,200 km2), Rancho Los Nietos, as a reward for his military service and to encourage settlement in California.[6] The area of Nieto's land grant was reduced in 1790 as the result of a dispute with Mission San Gabriel. Nonetheless, Nieto still had a claim to 167,000 acres (680 km2) stretching from the hills north of Whittier, Fullerton, and Brea, south to the Pacific Ocean, and from what is known today as the Los Angeles River east to the Santa Ana River. Nieto built a rancho for his family near Whittier, purchased cattle and horses for his ranch, and planted cornfields. When he died in 1804, his children inherited his property.

At the time of the 1840s Mexican–American War, much of the land that became Whittier was owned by Pio Pico, a rancher and the last Mexican governor of Alta California.[6] Pio Pico built a hacienda on the San Gabriel River, known today as Pio Pico State Historic Park.[6] After the war, German immigrant Jacob F. Gerkens paid the U.S. government $234 to acquire 160 acres (0.6 km2) of land under the Homestead Act and built the cabin known today as the Jonathan Bailey House.[10] Gerkens later become the Los Angeles Police Department's first chief of police. His land was owned by several others before a group of Quakers purchased it and expanded it to 1,259 acres (5 km2), intending to found a Quaker community. The area soon became known as a thriving citrus ranching region, with "Quaker Brand" fruit shipped all over the United States. Beginning in 1887, walnut trees were planted, and Whittier became the nation's largest walnut grower.[6][9] In addition to walnuts and citrus, Whittier was also a significant producer of pampas grass.

For many years, the sole means of transport from this area to Los Angeles was by foot or horse and wagon over rough dirt roads, impeding settlement, development, and the export of agriculture.[11] Thus in 1887 "enterprising and aggressive businessmen" contracted with the Southern Pacific Railroad to build the first railroad spur to Whittier, including a depot.[12] The businessmen covered the $43,000 construction cost for the six-mile spur, which branched off from the Southern Pacific mainline at a junction near what is now Studebaker Road between Firestone Boulevard and Imperial Highway.[13] By 1906, 650 carloads of oranges and 250 carloads of lemons were shipped annually by rail. In 1904, the Pacific Electric opened the trolley line known as "Big Red Cars" from Los Angeles to Whittier. In the first two decades, over a million passengers a year rode to and from Los Angeles on the Whittier Line.[6]

During the 1920s and 30s, Whittier was a conservative sundown town. New housing tracts such as College Hills were developed under restrictive covenants and minorities were restricted to areas outside the city limits such as Jimtown (portions of which were destroyed by the building of the 605 Freeway).[14] Whittier even had a branch of the Silver Shirts.[15] Liquor sales were forbidden in the city; Bailey's Liquor Store was just outside the city limits. Richard Nixon, though born and buried in Yorba Linda, grew up in East Whittier.[16] He attended and played football at Whittier High School (1928–30) and Whittier College (1930–34)[17] In the 1930s, Nixon's law office was in the National Bank of Whittier Building in Uptown Whittier. Upon Nixon's return from World War II service, conservative Whittier businessman Herman Perry, Nixon's former landlord at the bank, spearheaded an effort to form a Committee of 100 Republicans in Eastern Los Angeles County to get Nixon elected to Congress in 1946.

After World War II, Whittier grew rapidly. The subdividing of orange groves began, driven by housing shortages in southern California. In 1955, the Civic Center complex was completed, and the City Council met in new chambers for the first time on March 8, 1955. The city continued to grow as it annexed portions of Whittier Boulevard and East Whittier. The 1961 annexation added over 28,000 people to the population, bringing the total to about 67,000.[6] South and West Whittier remained unannexed by the city.

Quakers

[edit]

The first Quaker meetings were held on the front porch of the Jonathan Bailey House.[10] As more Quakers arrived, the need for an actual Quaker meeting house arose, and the first one was built in 1887 on the corner of Comstock Avenue and Wardman Street. The meeting soon outgrew this 100-seat meeting house, and a larger building was erected on the corner of Philadelphia Street and Washington Avenue in 1902. By 1912, membership had grown to 1,200, and a third building was dedicated on the same site in 1917. With a capacity of 1,700, the 1917 meeting house had a balcony and was constructed of brick with mahogany paneling and pews. The present meeting house, dedicated in 1975, has many architectural elements and materials from the 1917 building, including the stained glass windows and mahogany interior.[18] The Quakers also founded Whittier Academy (later Whittier College), and additional meetings met in East Whittier and at Whittier College's Mendenhall. The Mendenhall and East Whittier meetings kept the silent meeting longer than the main church.

Colleges

[edit]

In 1887, the Pickering Land and Water Company set aside a 20-acre (81,000 m2) parcel of land to develop a college, but a collapse in the land boom stalled construction. Progress on developing a college was sporadic, but on July 30, 1896, the Whittier Academy, operating since 1891, officially changed its name to Whittier College and enrolled 100 students. The school mascot is "The Poet." By 1906, Whittier College was an educational institution with laboratories, boarding halls, a large gymnasium, and athletic fields. Due to an economic depression in the 1890s, the first bachelor's degrees were not awarded at the college for 17 years.[6]

Leona May Mendenhall donated the Mendenhall Building at Whittier College in honor of her husband, Oscar. The Mendenhalls were among Whittier's founding families. Oscar's brother, Samuel Mendenhall, helped bring in the water system and post office. The Mendenhalls were major growers of Sunkist oranges and Blue Diamond walnuts.

Whittier was the first home to Azusa Pacific University, established in 1899 by the Quaker community and a Methodist evangelist under the name Training School for Christian Workers.[19]

Whittier Narrows earthquake

[edit]On October 1, 1987, at 7:42 a.m., the Whittier Narrows earthquake struck, the epicenter six miles (10 km) north-northwest of Whittier. The seismic event, which registered 5.9 on the moment magnitude scale, killed eight people and damaged many of uptown Whittier's historic buildings. Three days later, on October 4 at 3:59 a.m., a major aftershock measuring 5.2 caused further damage. Buildings and residential structures that were already borderline unsafe were now deemed unsafe or uninhabitable. In the years following the earthquake, the city's deteriorating uptown business district became the focus of renewed development, meeting opposition from many Whittier citizens. The Whittier Conservancy was formed in 1987 to stop the demolition of many historic buildings and residences after the disaster. The city also created a Historic Resources Commission to oversee the approval of landmark designations, historic districts, and Mills Act proposals. The Whittier Narrows earthquake destroyed The Quad at Whittier, a shopping mall that was rebuilt.

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 14.7 square miles (38 km2), virtually all land.

Whittier is bordered by Hacienda Heights to the northeast, City of Industry to the north, and several other unincorporated communities in the San Gabriel Valley mostly along its northern sections. Pico Rivera lies to the west, La Habra Heights to the east, La Habra to the southeast, and Santa Fe Springs to the south.

Neighborhoods

[edit]Whittier has several neighborhoods. The area around Philadelphia Street and Greenleaf Avenue is known as Uptown Whittier and contains the traditional central business core. Just north of it are the neighborhoods known as Central Park and Hadley-Greenleaf. They have been designated historic districts by the city Historic Resources Commission and comprise most of the Whittier Historic Neighborhood Association area. These districts contain many Craftsman and Spanish Colonial Revival homes. In and abutting the hills north of the historic districts is Starlite Estates. The area surrounding Whittier College is known as College Hills and was also recently designated a historic district, as it has a small cluster of homes along Earlham Drive. The area east of College Avenue is called East Whittier. It was an unincorporated agricultural community until the postwar era. The eastern part of East Whittier, developed in the 1950s and 1960s, is known as Friendly Hills, and was developed at the same time as Murphy Ranch and Leffingwell Ranch. Friendly Hills and Murphy Ranch are generally considered north of Whittier Boulevard, while Leffingwell Ranch is south of it. The area at the extreme east of Whittier is occasionally called Sunglow.

Climate

[edit]Whittier is about 15 miles (24 km) inland of the Pacific Ocean, resulting in higher daytime temperatures, and since it lies at a higher elevation than the cities further west, cold air drains into the lower elevation of the Los Angeles Basin, causing warmer nighttime lows, an example of thermal inversion. Winter daytime highs typically range from 57 °F to 72 °F (20 °C to 27 °C) with overnight lows dropping to about 41 °F to 50 °F (6° to 12 °C). In the summer highs range from 84 °F to 97 °F (26 °C to 35 °C) and corresponding overnight lows in the 62 °F to 70 °F (14 °C to 22 °C). Rainfall follows a Mediterranean pattern, with most falling during winter, while summers tend to be rather dry. The mean annual rainfall is about 14 inches (360 mm).

| Climate data for Whitter CA (Wx-Station located 4.5mi NNW at Montebello, CA 1971–2000 Normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 91 (33) |

95 (35) |

100 (38) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

108 (42) |

108 (42) |

106 (41) |

113 (45) |

106 (41) |

100 (38) |

88 (31) |

113 (45) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 69.7 (20.9) |

71.3 (21.8) |

72.6 (22.6) |

77.4 (25.2) |

79.2 (26.2) |

84.2 (29.0) |

88.9 (31.6) |

89.4 (31.9) |

87.5 (30.8) |

82.2 (27.9) |

75.2 (24.0) |

70.7 (21.5) |

79.0 (26.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 58.8 (14.9) |

60.0 (15.6) |

61.6 (16.4) |

65.3 (18.5) |

68.1 (20.1) |

72.6 (22.6) |

76.6 (24.8) |

77.4 (25.2) |

75.7 (24.3) |

70.3 (21.3) |

63.6 (17.6) |

59.0 (15.0) |

67.4 (19.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 47.9 (8.8) |

48.7 (9.3) |

50.5 (10.3) |

53.1 (11.7) |

56.9 (13.8) |

60.9 (16.1) |

64.3 (17.9) |

65.4 (18.6) |

63.8 (17.7) |

58.4 (14.7) |

52.0 (11.1) |

47.3 (8.5) |

55.8 (13.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 30 (−1) |

29 (−2) |

33 (1) |

39 (4) |

30 (−1) |

30 (−1) |

38 (3) |

44 (7) |

50 (10) |

44 (7) |

37 (3) |

30 (−1) |

29 (−2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.53 (90) |

3.60 (91) |

2.94 (75) |

0.90 (23) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.06 (1.5) |

0.01 (0.25) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.17 (4.3) |

0.31 (7.9) |

1.00 (25) |

1.67 (42) |

14.44 (367) |

| Source: http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/cliMAIN.pl?ca5790 [20] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 585 | — | |

| 1900 | 1,590 | 171.8% | |

| 1910 | 4,550 | 186.2% | |

| 1920 | 7,997 | 75.8% | |

| 1930 | 14,822 | 85.3% | |

| 1940 | 16,115 | 8.7% | |

| 1950 | 23,433 | 45.4% | |

| 1960 | 33,663 | 43.7% | |

| 1970 | 72,863 | 116.4% | |

| 1980 | 68,558 | −5.9% | |

| 1990 | 77,671 | 13.3% | |

| 2000 | 83,680 | 7.7% | |

| 2010 | 85,331 | 2.0% | |

| 2020 | 87,306 | 2.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[21] 1860–1870[22][23] 1880-1890[24] 1900[25] 1910[26] 1920[27] 1930[28] 1940[29] 1950[30] 1960[31] 1970[32] 1980[33] 1990[34] 2000[35] 2010[36] 2020[37] | |||

Whittier first appeared as a town in the 1890 U.S. Census;[24] and as a city in the 1900 U.S. Census.[25]

2020

[edit]The 2020 United States census reported that Whittier had a total population of 87,306 people with a density of 5,824.9 people per square mile. The racial makeup of the city was 48.7% White (24.5% Non-Hispanic white, 24.2% White Hispanic), 1.5% African American, 1.1% Native American, 5.3% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, and 8.4% from two or more races. Hispanic and Latino Americans were 65.8% of the population. 16.6% of the population were foreign born, and 3.1% of people were veterans.

There were 27,093 households, of which the average size was 3.07 persons. The median household income during 2016–2020 was $76,026, and 9.5% of the population was living in poverty.

The population was spread out, with 23.0% of the population under the age of 18 and 15.1% above the age of 65. Of all people aged above 25 years, 88.5% were high school graduates, and 26.7% had a bachelor's degree or higher. 61.5% of people aged above 16 years were in the civilian labor force.[4]

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[38] | Pop 2010[39] | Pop 2020[37] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 31,475 | 24,126 | 18,018 | 37.61% | 28.27% | 20.64% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 838 | 780 | 1,014 | 1.00% | 0.91% | 1.16% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 341 | 226 | 248 | 0.41% | 0.26% | 0.28% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 2,628 | 2,996 | 3,967 | 3.14% | 3.51% | 4.54% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 90 | 91 | 122 | 0.11% | 0.11% | 0.14% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 113 | 131 | 440 | 0.14% | 0.15% | 0.50% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 1,430 | 900 | 1,694 | 1.71% | 1.05% | 1.94% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 46,765 | 56,081 | 61,803 | 55.89% | 65.72% | 70.79% |

| Total | 83,680 | 85,331 | 87,306 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010

[edit]The 2010 United States Census[40] reported that Whittier had a population of 85,331. The population density was 5,818.6 inhabitants per square mile (2,246.6/km2). The racial makeup of Whittier was 55,117 (64.6%) White (28.3% Non-Hispanic White, 36.3% White Hispanic),[41] 1,092 (1.3%) African American, 1,093 (1.3%) Native American, 3,262 (3.8%) Asian, 123 (0.1%) Pacific Islander, 20,848 (24.4%) from other races, and 3,796 (4.4%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 56,081 persons (65.7%).

The Census reported that 83,696 people (98.1% of the population) lived in households, 1,083 (1.3%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 552 (0.6%) were institutionalized.

There were 28,273 households, out of which 11,289 (39.9%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 14,152 (50.1%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 4,566 (16.1%) had a female householder with no husband present, 1,896 (6.7%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 1,770 (6.3%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 247 (0.9%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 6,096 households (21.6%) were made up of individuals, and 2,495 (8.8%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.96. There were 20,614 families (72.9% of all households); the average family size was 3.46.

The population was spread out, with 21,686 people (25.4%) under the age of 18, 9,198 people (10.8%) aged 18 to 24, 23,627 people (27.7%) aged 25 to 44, 20,819 people (24.4%) aged 45 to 64, and 10,001 people (11.7%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.5 males.

There were 29,591 housing units at an average density of 2,017.8 per square mile (779.1/km2), of which 16,207 (57.3%) were owner-occupied, and 12,066 (42.7%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.3%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.1%. 49,393 people (57.9% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 34,303 people (40.2%) lived in rental housing units.

During 2009–2013, Whittier had a median household income of $68,522, with 12.4% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[41]

2000

[edit]As of the census[42] of 2000, there were 83,680 people, 28,271 households, and 20,468 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,719.4 inhabitants per square mile (2,208.3/km2). There were 28,977 housing units at an average density of 1,980.5 per square mile (764.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 43.2% White, 1.2% African American, 1.3% Native American, 3.3% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 25.8% from other races, and 5.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 65.9% of the population.[43]

There were 28,271 households, out of which 37.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.5% were married couples living together, 14.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.6% were non-families. 22.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.88 and the average family size was 3.38.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 28.3% under the age of 18, 10.0% from 18 to 24, 30.6% from 25 to 44, 18.6% from 45 to 64, and 12.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $49,256, and the median income for a family was $55,726. Males had a median income of $40,394 versus $34,223 for females. The per capita income for the city was $21,409. About 7.8% of families and 10.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.7% of those under age 18 and 8.0% of those age 65 or over.

Mexican and German were the most common ancestries. Mexico and El Salvador were the most common foreign places of birth.[44]

Homelessness

[edit]In 2022, Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority's Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count counted 127 homeless people in Whittier.[45]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 244 | — |

| 2017 | 203 | −16.8% |

| 2018 | 178 | −12.3% |

| 2019 | 283 | +59.0% |

| 2020 | 230 | −18.7% |

| 2022 | 127 | −44.8% |

| Source: Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority | ||

Economy

[edit]Whittier's Redevelopment Agency has numerous projects underway to revitalize the community. This includes a $7 million project near the Hoover Hotel and development of a 480-acre (1.9 km2) project area near Whittier Blvd. The city council adopted the master plan in 2005. In 2019, Whittier's first food hall, Poet Gardens, opened in Uptown Whittier.[46]

The Whittwood Town Center is a shopping destination in Whittier.

Top employers

[edit]According to the city's 2013 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[47] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Presbyterian Intercommunity Hospital | 2,600 |

| 2 | Whittier Union High School District | 950 |

| 3 | Whittier Hospital Medical Center | 850 |

| 4 | Whittier City School District | 720 |

| 5 | City of Whittier | 621 |

| 6 | United States Postal Service | 360 |

| 7 | Bright Health Physicians | 300 |

| 8 | Ralph's | 270 |

| 9 | Los Angeles County |

Arts and culture

[edit]On April 17, 1900, the Whittier Public Library Board of Trustees held its first meeting in Landrum Smith's drugstore. With an initial collection of 60 books and 200 magazines, the library facilities began in the Woody Building as a reading room maintained by Hester in exchange for space for his telegraph office. In 1907, a Carnegie grant funded building construction at Bailey and Greenleaf that many Whittierites fondly remember. As the city expanded, a more extensive library was needed, and the Friends of the Library was organized in 1956 to raise money for a new building. Through their efforts and those of the board members, librarians, and citizen fundraising groups, the new library was completed at the Washington Avenue site in May 1959. In 1968, service was further expanded with the construction of the Whittwood Branch Library on Santa Gertrudes Avenue.[48]

Historical landmarks and entertainment locations

[edit]

- Rose Hills Memorial Park, the largest single-location cemetery in the world, is located just outside the city western edge in unincorporated Whittier.[49]

- Whittier is home to the following California Historical Landmarks[50]

- Pio Pico State Historic Park, California Historical Landmark No. 127: The Casa de Governor Pío Pico/Home of Governor Pío Pico, home of the last Mexican Governor of California.

- California Historical Landmark No. 646: Grave of George Caralambo, (Greek George). Grave marker is located at the Whittier Museum :

- California Historical Landmark No. 681: Paradox Hybrid Walnut Tree:

- California Historical Landmark No. 947: Reform School for Juvenile Offenders (Fred C. Nelles School — Closed May 27, 2004, and currently being redeveloped for business and residential use)

- Whittier Museum - 6755 Newlin Ave, Whittier 90601. Open for public tour Fridays and Saturdays from 1 to 4 p.m. and is free of charge[51]

- Whittier is the home to the following places listed in the National Register of Historic Places:

- Pio Pico House, 6003 Pioneer Blvd.

- Hoover Hotel, 7035 Greenleaf Ave.

- Southern Pacific Railroad Depot, 7333 Greenleaf Ave.

- Standard Oil Building, 7257 Bright Ave.

- Jonathan Bailey House, 13421 E. Camilla St.

- National Bank of Whittier Building, 13002 E. Philadelphia

- Orin Jordan House, 8310 S. Comstock Ave.

Government

[edit]City government

[edit]Whittier uses a council–manager form of government. Until 2014, all five city council members were elected at-large, with the mayor being elected by the council. Following the 2016 elections, four city council members were elected to four-year terms in districts, whereas the mayor was directly elected to two-year terms. The council also appoints a city manager.[52]

The current mayor of Whittier is Joe Vinatieri.[53] The city council is currently made up of Fernando Dutra, Octavio Martinez, Cathy Warner, and mayor pro tempore Jessica Martinez.[54] Brian Saeki is serving as the city manager and Shannon DeLong as the assistant city manager.[55]

Federal and state representation

[edit]In the California State Legislature, Whittier is in the 30th Senate District, represented by Democrat Bob Archuleta, and in the 56th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Lisa Calderon.[56]

In the United States House of Representatives, Whittier is in California's 38th congressional district, represented by Democrat Linda Sánchez.[57]

Education

[edit]

The following school districts serve the city of Whittier:[58]

- Fullerton Joint Union High School District

- Whittier Union High School District

- East Whittier City School District

- Los Nietos School District

- Lowell Joint School District

- South Whittier School District

- Whittier City School District

Five high schools, California High School, La Serna High School, Pioneer High School, Santa Fe High School, and Whittier High School comprise the Whittier Union High School District. There is one alternative continuation high school Frontier High School and a homeschooling hq, Sierra Vista High School. Although they still have Whittier postal addresses, both California High School and Pioneer High School lie outside the city limits in unincorporated Los Angeles County. Santa Fe High School is located within the City of Santa Fe Springs. Adults may attend the Whittier Adult School, which belongs to the Whittier Union High School District. The city also has three private Catholic elementary schools, K-8:

- St. Bruno's Parish School[59]

- St Gregory The Great Parish School[60]

- St. Mary of the Assumption School[61]

The schools are operated by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles. One (St. Mary of the Assumption School) is one of the largest Catholic elementary schools in Los Angeles County. St Gregory The Great School has been Number One in their deanery for the Academic Decathlon two consecutive years.

Whittier Friends School[62] is a member of the Friends Council on Education[63] and associated with First Friends Church of Whittier,[64] the founding Quaker meeting of Whittier. Whittier Friends School includes a licensed preschool and an elementary school (TK-6th grade).

Trinity Lutheran School,[65] a ministry of Trinity Lutheran Church, serves kindergarten through eighth grade.

Whittier Christian School,[66] a ministry of Calvary Baptist Church, Association of Christian Schools International serves the Whittier community. They have an elementary campus, two preschool campuses, a junior high school, and a high school.

Plymouth Christian School,[67] a ministry of Plymouth Church, serves preschool through sixth grade.

Higher education institutions in the area include Rio Hondo College, which lies just outside the city, Southern California University of Health Sciences, and historic Whittier College.

Media

[edit]The local newspaper is the Whittier Daily News. Other area papers include the San Gabriel Valley Tribune (the parent paper of the Whittier Daily News), the Los Angeles Times, and the Orange County Register. The Music fanzine Flipside was published locally from 1977 to 1990. Former newspapers include the Coast Reporter, Whittier Californian, Whittier Graphic, and the Whittier Star Reporter.[68][69]

Infrastructure

[edit]The Los Angeles County Department of Health Services operates the Whittier Health Center in Whittier.[70]

The California Youth Authority operated the Fred C. Nelles Youth Correctional Facility[71] from 1890 until it closed in 2004.[72]

Transportation

[edit]

Various bus routes operate in Whittier. Metro, Foothill Transit, Montebello Bus Lines, and the Norwalk Transit are the main ones. Foothill Transit line 274 originates at Beverly & Norwalk and proceeds north to Baldwin Park via Workman Mill Road and Puente Avenue. Foothill Transit line 285 travels through Whittier on Whittier Boulevard and Colima Road between La Habra and Hacienda Heights. Montebello Transit Line 10 originates at Whittwood Mall and proceeds west to Montebello and the Atlantic L Line station via Whittier Boulevard. Montebello 40 originates at Beverly and Norwalk and proceeds west to Montebello and Downtown Los Angeles via Beverly Boulevard and 4th Street. Montebello 50 travels through Whittier between La Mirada and Downtown Los Angeles. Metro Bus line 120 originates at Whittwood Mall and travels west to the Norwalk C Line station, then to the Aviation C line station via Imperial Hwy.

Whittier also has a variety of roads. One freeway, the San Gabriel River Freeway (I-605), runs along the city's northern end. State Route 72 runs via Whittier Boulevard and forms part of El Camino Real. Other major streets in Whittier include Beverly Boulevard, Colima Road, Greenleaf Avenue, Lambert Road, Mar Vista Street, Mills Avenue, Norwalk Boulevard, Painter Avenue, Philadelphia Street, and Washington Boulevard.

Police

[edit]The Whittier Police Department provides law enforcement services.

Fire

[edit]There are three fire stations within Whittier city limits: Los Angeles County Fire Department Station 28 (Engine, Quint, Paramedic Squad, Mobile Aid, and the Battalion Chief), Station 17 (Engine), and Station 59 (Engine and IRT).[73]

Fred C. Nelles Youth Correctional Facility

[edit]The Fred C. Nelles Youth Correctional Facility served as a state reform school for boys and girls until 1916 when the girls were moved elsewhere. Opened in 1891, before Whittier was incorporated, Nelles was California's longest-running state school for juvenile offenders and has been declared a California State Historical Landmark. It closed in 2004, and the facility was used as a television filming site. In 2014, Brookfield Residential Properties announced plans for a large retail, commercial and residential project on the site. Much of Whittier is built out, so the 74-acre (30 ha) site brings a unique chance for growth in the city. Although over 50 buildings were demolished, discussions have focused on how many of the eight historic buildings should be preserved.[74] The administration building that was constructed in 1928–29 has a historical designation. Housing and commercial space are under construction on the site.[75]

Notable people

[edit]- George Allen, former Virginia governor and U.S. Senator

- Glenn Allison, professional ten-pin bowler and member of the PBA and USBC Halls of Fame

- Edson Alvarado, soccer player

- Deborah Babashoff, swimmer

- Shirley Babashoff, swimmer, winner of eight Olympic medals

- Andrea Barber, actress, Full House/Fuller House

- Mitch Callahan, former prospect for the Detroit Red Wings

- Raymond F. Chandler III, SMA, US Army, former Sergeant Major of the US Army

- Carl Cheffers, NFL referee

- Tricia Nixon Cox, daughter of President Richard Nixon

- Jeff B. Davis, comedian and actor

- Justin De Fratus, pitcher for Philadelphia Phillies

- M.F.K. Fisher, food writer[76]

- Nomar Garciaparra, professional baseball player[77]

- Jeff Loveness, American screenwriter and producer

- John Gay, screenwriter

- Matt Gourley, American comedic actor, writer, and teacher

- Greg Hancock, American Speedway rider

- Wally Hood, baseball player, member of Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame

- Lou Henry Hoover, wife of U.S. President Herbert Hoover[78]

- Gabriel Iglesias, comedian

- Tinker Juarez, professional cyclist, two-time Olympian, MTB Hall of Fame, BMX Hall of Fame, national champion, World Master MTB Champion[79]

- Melissa King, chef specializing in modern Californian cuisine, finalist on Top Chef: Season 12

- Mark Kostabi, artist and composer

- Paul Kostabi, artist and musician

- John Lasseter, co-founder of Pixar Animation Studios and film director

- Carey Lovelace, art writer and curator

- Gary Miller, Republican U.S. Representative for California's 31st congressional district. Miller grew up in Whittier.[80]

- Pat Nixon, First Lady of the United States, wife of Richard Nixon, whom she met while teaching English at Whittier High School

- Richard Nixon, 37th President of the United States

- Dax Reynosa, a hip-hop and smooth jazz musician and producer

- Zane Reynosa, hip hop musician and fashion accessory designer

- Douglas Robinson, professor of English, dean

- Michael Vernon Robinson, automobile designer

- John Saul, suspense and horror novelist

- Ron Shelton, film director and screenwriter

- Lauren Tewes, actress, grew up in Whittier

- Stu Thomsen, professional BMX racer

- Aaron Valdes (born 1993), basketball player in the Israeli Basketball Premier League

- Melissa Villaseñor, comedian, actress and singer

- Tom Waits, musician, composer, songwriter and actor

- Jessamyn West, author of The Friendly Persuasion[78]

- Del Worsham, NHRA funny car and top fuel driver, 2011 Top Fuel World Champion

- Tina Yothers, actress and singer

- Wendell "Bud" Hurlbut, amusement park designer

Film and television locations

[edit]Various notable movies and television shows have been filmed in the city, including:

- Gardens of the Night (2008) – Film starring Gillian Jacobs, John Malkovich, Ryan Simpkins and Tom Arnold. Scenes were filmed in Michael's Super Burgers.

- Masters of the Universe (1987) - Film starring Frank Langella. Key battle scenes in a music store and on rooftops during Skeletor's invasion of Earth were shot here, among others.[81]

- Amish Grace (2010) – Television film. The carriage procession was filmed on Greenleaf St. in Uptown Whittier, and the funeral home scene was filmed at The Good Shepherd Family Bible Church, across the street from the post office on Bailey St.

- Back to the Future (1985) and Back to the Future Part II (1989) – Films starring Michael J. Fox. Whittier High School was used as the setting for Hill Valley High School.

- Hocus Pocus (1993) – Film starring Bette Midler, Sarah Jessica Parker, Thora Birch and Vinessa Shaw. Parts were filmed in Uptown Whittier and East Whittier Middle School.

- Father of the Bride Part II (1995) – Film starring Steve Martin. Parts were filmed in uptown Whittier.

- The Wonder Years (1988–1993) – Television series starring Fred Savage. The parade scene in the last episode was filmed in uptown Whittier.

- The Next Best Thing (2000) – Film starring Madonna and Rupert Everett was filmed in the Whittier Hills.

- Bringing Down the House (2003) – Film starring Queen Latifah and Steve Martin was filmed at the Friendly Hills Country Club, in East Whittier.

- Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (2003) – Film starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Various parts were shot in Whittier, including in Rose Hills Memorial Park.

- Blow (2001) – Film starring Johnny Depp and Penélope Cruz. Scenes were filmed at the Fred C. Nelles Youth Correctional Facility, which closed in January 2004, and in a residential neighborhood.

- Ali (2001) – Directed by Michael Mann, portions of which were filmed at a residence in the historic neighborhood near the uptown village.

- Disturbia (2007) – Film starring Shia LaBeouf, Carrie-Anne Moss, and Amanda Walsh. Was shot on Painter Ave, the deli scenes were filmed at "Our Cleaners" on Comstock Ave. in uptown Whittier.

- Moonlight (2007–2008) – Television series starring Alex O'Loughlin and Sophia Myles. Exteriors of a state execution facility were filmed at the Fred C. Nelles Youth Correctional Facility; the facility name is clearly shown in multiple shots.

- What Just Happened? (2008) – Film starring Robert De Niro, Bruce Willis, Sean Penn and Robin Wright Penn. Scenes were filmed in Rose Hills Memorial Park.

- Red State (2011) – Film directed by Kevin Smith and starring Michael Parks. Scenes were filmed at the Fred C. Nelles Youth Correctional Facility and Trinity Lutheran Church.

- True Blood (2008–2014) – Several scenes involving The Fellowship of the Sun church were filmed at the chapel at Rose Hills Memorial Park. On the DVD commentary of Season 3, Stephen Moyer says several local girls came to the filming with shirts saying, "The girls are prettier in Whittier".

- Roadracers (1994) – Film starring David Arquette, John Hawkes, and Salma Hayek; directed by Robert Rodriguez. Much of the filming occurred in Uptown, the nearby residential neighborhoods, and Turnbull Canyon Road. John Hawkes describes in an interview, "We shot anywhere we could find something that looked like the 1950s. It was difficult near L.A. It was hard to find things that looked authentic to the period and a small Texas town. I think they did a good job finding [the locations]."[82]

- The Muppets (2011) – Film starring Amy Adams and Jason Segel. Scenes at the beginning of Walter and Gary's hometown were shot in a historic Uptown Whittier residential area.

- Old Boyfriends (1979) - Film starring Talia Shire, Richard Jordan, Keith Carradine, John Belushi, John Houseman and Buck Henry. Scenes with Talia Shire and Keith Carradine were shot near Central Park in historic Uptown Whittier.

- The Little Things (2021) – Film starring Denzel Washington, Rami Malek, and Jared Leto. Scenes were shot in uptown on Bright Ave.

Sister cities

[edit]See also

[edit]- South Whittier, California (an unincorporated area south of the city limits)

- West Whittier-Los Nietos, California (an unincorporated area west of the city limits)

- East Whittier, California (an unincorporated area east of the city limits)

- Rose Hills, California (an unincorporated area north of the city limits)

- Paradox Hybrid Walnut Tree in Whittier

References

[edit]- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Whittier". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Whittier city, California; United States". United States Census Bureau. April 1, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ "ZIP Code(tm) Lookup". United States Postal Service. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Whitter Web - Homepage". Cityofwhittier.org. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ^ "The Barefoot Boy by John Greenleaf Whittier". Poetry Foundation. April 7, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "A Brief History of Whittier to 1970". City of Whittier. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ^ a b [1] Archived February 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Points of Interest". City of Whittier. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ^ Arnold, Benjamin F.; Clark, Artilissa Dorland (1933). History of Whittier. Whittier, California: Western Printing Corporation. p. 19.

- ^ Arnold and Clark, 20

- ^ Church, William. "A Brief History of the Southern Pacific Railroad in Whittier". Whittier Museum and Historical Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ "Dick Nixon's Orange County". OC Weekly. August 5, 1999.

- ^ Steven Ross. Hitler in Los Angeles: How Jews Foiled Nazi Plots Against Hollywood and America. p. 83.

- ^ R. W. Apple Jr. (April 23, 1994). <0A15757C0A962958260 "THE 37th PRESIDENT - RICHARD NIXON, 81, DIES - A MASTER OF POLITICS UNDONE BY WATERGATE - Obituary; Biography - NYTimes.com". The New York Times. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ^ "Richard M. Nixon | The White House". Whitehouse.gov. March 11, 2011. Archived from the original on March 12, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ^ Nelson, Carl (1975). Whittier Friends Church: Eighty-Eight Years of Service. Library of William Wright: First Friends Church. pp. 2–9.

- ^ "Timeline - About APU - Azusa Pacific University". www.apu.edu. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ WRCC. "Western U.S. Climate Historical Summaries Weather". Desert Research Institute. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ "Decennial Census by Decade". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1870 Census of Population - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties - California - Almeda County to Sutter County" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1870 Census of Population - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties - California - Tehama County to Yuba County" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "1890 Census of Population - Population of California by Minor Civil Divisions" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "1900 Census of Population - Population of California by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1910 Census of Population - Supplement for California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1930 Census of Population - Number and Distribution of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1940 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1960 Census of Population - General population Characteristics - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1970 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1980 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2000 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2010 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Whittier city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Whittier city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Whittier city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Whittier city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "Whittier (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/QTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=16000US0685292&-qr_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U_QTP3&-ds_name=D&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today factfinder.census.gov

- ^ "Whittier Profile - Mapping L.A. - Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Homeless Count by City/Community". LAHSA. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "EPISODE 103: BUILD UP OUR UPTOWN with Ricardo Diaz". What's Up Whittier. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "City of Whittier CAFR".

- ^ [2] Archived March 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Home". Rose Hills. Archived from the original on January 4, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ^ "Los Angeles". Ohp.parks.ca.gov. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ "Home". Whittier Historical Society & Museum. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ^ "City Council". City of Whittier. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Mayor Joe Vinatieri". City of Whittier. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "City Council Profiles". City of Whittier. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "City Manager". City of Whittier. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Final Maps". We Draw the Lines CA. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ "California's 38th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ "The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States - Statistical Atlas".

- ^ "Home". Saintbrunoschool.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ^ "Squarespace - Account Not Available". Stgregorywhittier.org. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ "St. Mary of the Assumption School in Uptown Whittier, California". saintmaryoftheassumptionschool.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Welcome to Whittier Friends School". www.whittierfriendsschool.org. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Friends Council on Education -> Home". friendscouncil.org. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Whittier First Friends Church". www.firstfriendswhittier.org. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Home - Trinity Lutheran Church of Whittier". trinitywhittier.360unite.com. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Home - Heights Christian Schools". Heights Christian Schools. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Plymouth Christian School". Plymouth Christian School. Archived from the original on November 24, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Newspaper, 1921, Los Angeles, Whittier". Library of Congress. Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ "The Availability of All Whittier Newspapers". Local History. Whittier Public Library. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ "Whittier Health Center." Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Institutions & Camps." California Youth Authority. January 25, 1998. Retrieved on August 10, 2010.

- ^ "States Closing Youth Prisons as Arrests Plunge." Associated Press. June 7, 2010. Retrieved on August 10, 2010.

- ^ "News | Whittier, CA". www.cityofwhittier.org. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ Mejia, Brittny (November 2, 2014). "Whittier sees hope in plan to transform historic Nelles property". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Sprague, Mike (October 22, 2018). "Nelles update: Former Whittier youth prison is on its way to becoming this". Whittier Daily News. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ Reardon, Joan (2004). Poet of the Appetites: The Lives and Loves of M.F.K. Fisher [Hardcover]. North Point Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-86547-562-5.

- ^ "Anthony Nomar Garciaparra". Baseball Reference. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ a b "Whittier California Profile and Resource Guide, City or community of Whittier, California Facts, Information, Relocation, Real Estate, Advertising". Usacitiesonline.com. February 28, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ^ "home". Tinkerjuarez.com. March 4, 1961. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ^ Barone, Michael; McCutcheon, Chuck (2013). 2014 Almanac of American Politics. The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ "Masters of the Universe Movie Filming Locations - The 80s Movies Rewind". www.fast-rewind.com. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "'Roadracers' Star John Hawkes Talks Making the Movie - Yahoo Movies". Archived from the original on December 4, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ "Sister City Program - Changshu, China", Whittier, CA - Parks, Recreation and Community Services, retrieved June 21, 2023